What is Blue Light?

Blue light is a type of visible light with wavelengths between 380–500 nanometers. It exists in two primary forms:

- Beneficial blue light: Naturally emitted by the sun, this type of blue light regulates melatonin production during the day, supports the circadian rhythm, and enhances alertness. As a result, it helps improve focus and maintain a balanced sleep-wake cycle (Brainard et al., 2001).

- Harmful blue light: Artificial blue light emitted by electronic devices such as smartphones, tablets, computers, and televisions. Exposure to artificial blue light—especially during the evening—can disrupt biological rhythms and lead to various health issues (Cajochen et al., 2011).

⸻

Daily Exposure to Blue Light

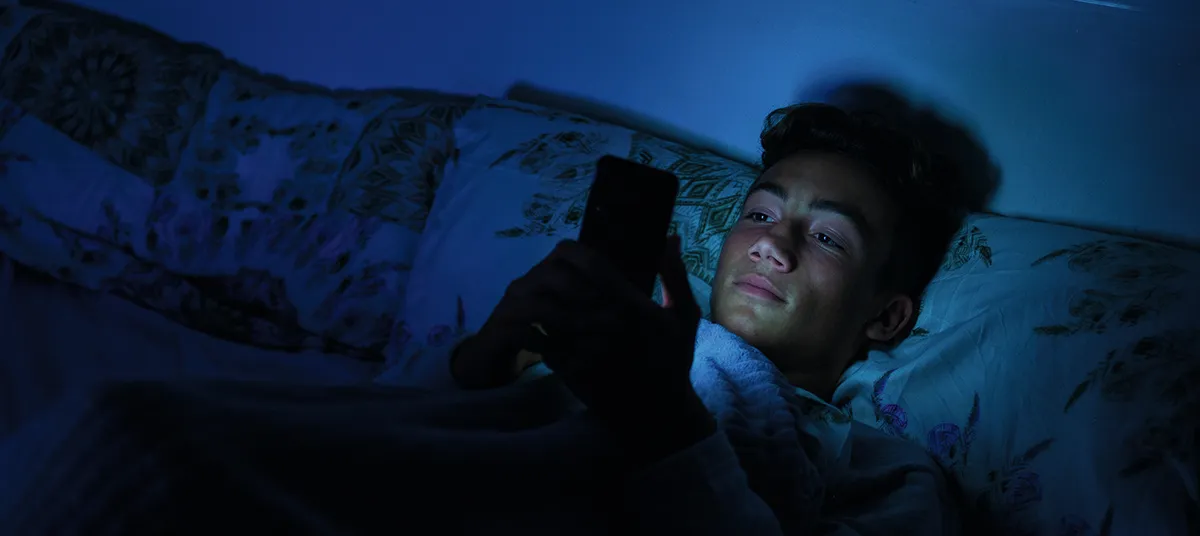

For many, the day begins by looking at a phone immediately upon waking—whether to check the time, read emails, or scroll through social media. Students and office workers often spend the majority of their day in front of computers or tablets, followed by evening hours watching TV or using phones.

Using these devices without adjusting brightness, especially in dark environments, significantly increases harmful blue light exposure. Older adults, who may spend long hours sitting and watching television, are also at high risk of both physical inactivity and prolonged blue light exposure.

⸻

Health Effects

- Circadian rhythm disruption: Blue light suppresses melatonin secretion, disrupting the body’s biological clock. This makes it harder to fall asleep at night and more difficult to wake up in the morning (Chang et al., 2015).

- Eye health problems: Prolonged exposure increases the risk of dry eyes, contributes to myopia progression, and may raise the risk of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) (Behar-Cohen et al., 2011).

- Skin aging: Blue light can cause collagen and elastin breakdown, leading to premature skin aging, sagging, and pigmentation issues (Osborne et al., 2020).

- Increased risk of eye diseases: Long-term exposure has been linked to cataract formation, macular damage, and, in rare cases, eye cancer (Wu et al., 2016).

⸻

Protection Strategies

- Limit the use of electronic devices, especially in the evening.

- Install blue light filtering software or enable “night mode/sunset mode” on devices.

- Adjust screen brightness based on ambient light, lowering it in the evening.

- Use blue light-blocking glasses or glasses with yellow/orange-tinted lenses to help the brain correctly perceive day-night cycles.

- Moisturize skin regularly to counteract dryness caused by prolonged screen exposure.

⸻

Conclusion

Blue light from natural sources during the day benefits our circadian rhythm and alertness. However, artificial blue light from electronic devices—particularly in the evening—can negatively impact sleep, eye health, and skin condition. Adjusting screen habits and applying protective measures can help minimize these risks.

⸻

References

- Behar-Cohen, F., et al. (2011). Light-emitting diodes (LED) for domestic lighting: Any risks for the eye? Progress in Retinal and Eye Research, 30(4), 239–257.

- Brainard, G. C., et al. (2001). Action spectrum for melatonin regulation in humans: evidence for a novel circadian photoreceptor. The Journal of Neuroscience, 21(16), 6405–6412.

- Cajochen, C., et al. (2011). Evening exposure to a light-emitting diodes (LED)-backlit computer screen affects circadian physiology and cognitive performance. Journal of Applied Physiology, 110(5), 1432–1438.

- Chang, A. M., et al. (2015). Evening use of light-emitting eReaders negatively affects sleep, circadian timing, and next-morning alertness. PNAS, 112(4), 1232–1237.

- Osborne, N. N., et al. (2020). Blue light and the eye: ocular and systemic effects. Eye, 34, 1953–1961.

- Wu, J., et al. (2016). Blue light-induced retinal photochemical damage: evidence from in vivo and in vitro studies. International Journal of Ophthalmology, 9(1), 81–88.